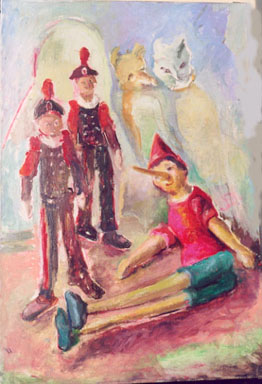

Another reason to hate the Mouse (or Copyright terms: Growing longer than Pinocchio's nose)

The Hall of Hate is my proposed name for a website detailing all the things and people that I detest. (Profiles in Loathing is the proposed subtitle.) If the ribbon is ever cut on the grand opening of this Hall, you can bet that Disney will be one of the inaugural entries.

The Hall of Hate is my proposed name for a website detailing all the things and people that I detest. (Profiles in Loathing is the proposed subtitle.) If the ribbon is ever cut on the grand opening of this Hall, you can bet that Disney will be one of the inaugural entries.

I usually don't have to think too hard to come up with a reason to hate Disney. I thought of a specific one a couple of days back that I haven't ever seen framed quite this way. As we all know, Disney is one of the most vigorous defenders of its company's copyrights. And of course, Disney made its own reputation on animated films adapted from 19th century works that had passed into the public domain. Everybody knows that. I'm not telling you anything new. But here's the specific example I'm thinking of:

Disney's animated adaptation of Pinocchio was made in 1940, 50 years after the death of the book's author, Carlo Collodi. Was it public domain at this point? Not quite; although the Berne Convention (the prevailing international copyright law both then and now) set the term of copyright as 50 years after the death of the author, Collodi didn't die until late October of 1890, and the Disney film was out in early February of 1940. It's kind of a moot point, though; the US wasn't a signatory to the Berne Convention yet, and routinely allowed US authors to break foreign copyrights.

But for the sake of argument, let's say that Pinocchio followed all the rules and was free to avoid paying royalties to Collodi's estate, because at least as far as US copyright law of the time was concerned, it did and it was. Certainly, this is a sterling example of why copyrights should have a fixed length: To allow the creation of derivative works. Pinocchio, like a great many early Disney films, shows that a derivative work can be a great work of art in its own right, not to mention a milestone in animation and film in general.

So I've got no problem with Pinocchio. Maybe I ought to, since I've got a big problem with Disney's The Hunchback of Notre Dame for drastically changing the plot to make Quasimodo friends with everyone and give everyone a happy ending when, in the Victor Hugo book, everyone shunned Quasimodo and everybody dies in the end except the goat, who got the only happy ending. In the original Pinocchio, the eponymous puppet fatally crushes Jiminy Cricket underfoot and is eventually hanged for his sins. But I don't have as much of a problem with this, since I grew up with and am most familiar with the Disney version, so it doesn't seem as much like a perversion of the original. And yet, that's exactly my problem with Hunchback: A future generation of children will grow up thinking the Disney abomination is the real deal.

So in fact, I do have a problem with Disney's Pinocchio, at least in principle, but let's stick with the copyright thing. For the sake of argument, we're saying that Pinocchio stuck to the rules, or came close enough.

Enter the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, which is commonly nicknamed "The Mickey Mouse Protection Act." Aghast at the prospect of Mickey Mouse and other beloved characters passing into the public domain -- and out of Disney's corporate clutches -- where a new generation of creators could base derivative works upon them without paying Disney a red cent, the company furiously and successfully lobbied for an extension of copyright by twenty years. The term of copyright in the US went from the author's life plus 50 years to life plus 70 years in the case of individual works (such as Collodi's Pinocchio, which still falls into the public domain under the new law) and from 75 years to 95 years in the case of works of corporate authorship (such as Disney's Pinocchio, which gets its due date extended from 2015 to 2035).

Let's go back to 1940. If the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act had been active then (and of course it would have had to have been called something else, as Bono wasn't as influential in congress at age 5), Collodi's copyright wouldn't have been due to expire until 1960. That means that, at best, Disney's film version couldn't have been made without paying royalties to the author's estate. At worst, Collodi's estate could have blocked Disney's version altogether.

Clearly, copyright is a good thing when it's in Disney's interest, but not when it's not. Happily, Mickey Mouse and all works created before 1970 are now public domain in Russia, at least. So if any Russian out there wants to create a vastly inventive derivative work based on any of this stuff, knock yourself out. And if you're not Russian, but you've got some real guts, a platoon of lawyers, and unlimited financial resources to battle Disney, feel free to create derivative works based on the original Mickey Mouse shorts; a recent law review journal article argues that despite the CTEA, they're in the public domain now and always were!

1 Comments:

Modest Mouse sux too. U R GAY!

Post a Comment

<< Home